As the world assesses what will change after the COVID-19 pandemic, Jim Cielinski, Global Head of Fixed Income, introduces the questions Janus Henderson expects to be key in setting investment strategy going forward.

We seek to share the insights of our investment teams to help inform our clients and, in the months ahead, will use these questions as a guide for our asset class leaders and investment teams to provide their views on whether we are likely to head down a positive or negative fork in the road.

Key Takeaways

- Change in the wake of any crisis is a given, and the volatility and stress associated with a crisis typically provide the catalyst to accelerate disruptive trends. But, as people, many of us will simply find different ways to do the same things.

- As investors, we contend that there is no feasible way to return to the paradigm of old after COVID-19. The unprecedented policy response and the aftershocks of staggering debt issuance indicate the economic world may never quite be the same.

- In today’s period of genuine uncertainty where the answer to many critical investment-related questions is binary, asking the right questions and focusing on both risks and opportunities will be essential to navigating the investment landscape.

Every crisis brings change. The COVID-19 coronavirus will be no different. It will alter the ways in which we interact, redefine how policy makers respond, and upend geopolitics and financial markets. However, there is much disagreement over how these changes will unfold, and never before have the answers to so many critical investment-related questions been so binary. Understanding these key issues will be essential for navigating the future investment landscape.

A break from, or return to, the norm?

Predictions during crises are notoriously bad. Humans tend to fixate on how we will be forced to change the way we live and interact with one another. We surmise that travel will never be the same, we will not eat out as often, and half of us will forever work from home. But more often than not, humans seek a return to a comfort zone and strive to replace the things they enjoyed. If past crises are a guide, in 12 to 18 months, most of us will be doing many of the same things that we were doing six months ago.

There will be changes, of course. Disruptive trends tend to accelerate in times of crisis, and the volatility and stress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic will likely provide a catalyst to prompt rapid modifications in behaviour. The shopping experience, for one, may never quite be the same as trends in place pre-crisis take a firmer grip in the years ahead.

Most changes, however, will be designed to facilitate a return to the norm. For example, there were countless predictions that air travel would plummet in the wake of the 9/11 disaster. Instead, air travel soared to record levels, but there were large-scale adjustments in how airports and security functioned to permit that swift return. Likewise, we will still watch movies in a year’s time, although much more of that may be via at-home digital streaming than in cinemas. While that is critical for the streaming services and cinema companies, the consumption of movies in aggregate may not change by much.

As people, we will find different ways to do the same things. But as investors, we contend that there is no feasible way to return to the paradigm of old.

Two areas where there is no going back

Speculation on how COVID-19 could impact our lifestyles may continue to dominate headlines, but it is critical for investors to look more broadly; many more important questions await.

Clearly, the path of the virus, the duration of shutdowns, and progress in testing, treatments, and vaccine development for COVID-19 will dictate market movements in the short term. Volatile markets force us to adopt an immediacy bias. But looking longer term, there are two things that indicate the economic world will never quite be the same. One, the policy response to this crisis has reminded us that policy makers are never truly out of tools, as had been suggested recently. Two, the aftershocks of the staggering amount of debt issuance will likely linger for decades.

A new era for policy makers

Crises are known to produce irreversible changes to monetary and fiscal policy and geopolitics. Policy responses are unpredictable – the impact of policy even more so. And with each crisis, a concept previously occupying the “lunatic fringe” moves ever closer to the norm. In 2007, how many people were predicting negative rates and $5 trillion of quantitative easing?

Speaking of negative rates, they have not been the panacea policy makers had hoped for. This will put continued pressure on quantitative easing to combat the economic contraction, essentially blurring the lines of where central bankers are simply lending money to corporate borrowers. We are entering a new era of direct intervention in asset and lending markets.

In less than three months, we have witnessed monetary policy break all bounds of what was considered possible, and fiscal policy is there to accompany it. After taking a backseat to monetary policy in recent years, fiscal policy has vaulted into the lead: mega-deficits are the new normal.

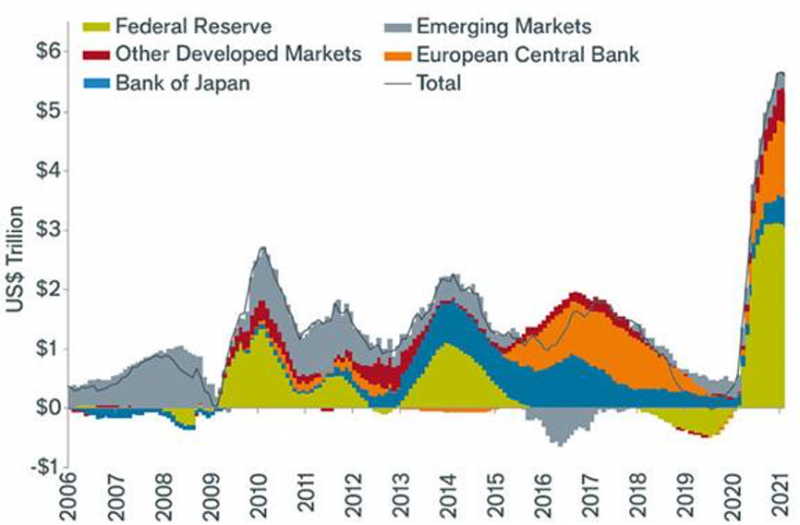

Total central bank purchases

The policy response to the economic slowdown resulting from the spread and containment of COVID-19 is unprecedented.

Mountains of debt

The lingering effect of that debt is the other “no going back” feature of this crisis. In 2008, there was an astonishing amount of debt issued to rescue economies from the Global Financial Crisis. Many called for the end of the debt supercycle as debt loads exploded to perceived unsustainable levels. But the decade since has shown that debt was, in fact, sustainable. As debt yet again soars to new records, will that still hold true?

Debt is not inherently bad. If the real return on assets is greater than financing costs, debt can provide a strong tailwind for growth. This is true for governments, corporations, and individuals. Equally, by helping to underwrite consumers and companies in times of stress, central banks can reduce the risk of higher debt loads and encourage more borrowing.

On the other hand, debt is the equivalent of ‘dis-saving’. And an economic identity holds that for every dis-saver, there must be a saver to fund it. This is the risk in a large global shock, as the swing to dis-saving by global governments has been surprisingly large. Will anyone be left to provide the global savings to address this growing imbalance? The answer to that question will tell us much about inflationary expectations, productivity, and wealth inequality.

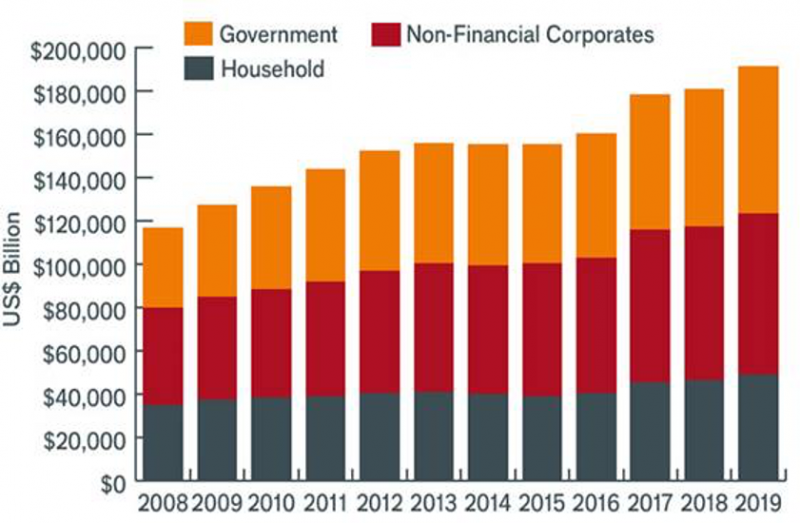

Global debt load

Driven primarily by corporate and government borrowers, global debt loads have increased steadily since the Global Financial Crisis.

The questions ahead for investors

The severity of the current slowdown is unprecedented. The policy response has been equally unprecedented. Both have led to increased uncertainty and more questions than answers. Markets are simply never the same after crises like these, and that is probably one prediction that will turn out to be true.

But as investors, it is often more important to ask the right questions than to have all the answers. Knowing which questions to ask is a first step to identifying the signposts for navigating volatility. And it helps to centre the mind on the factors that will truly drive markets in the months and years ahead.

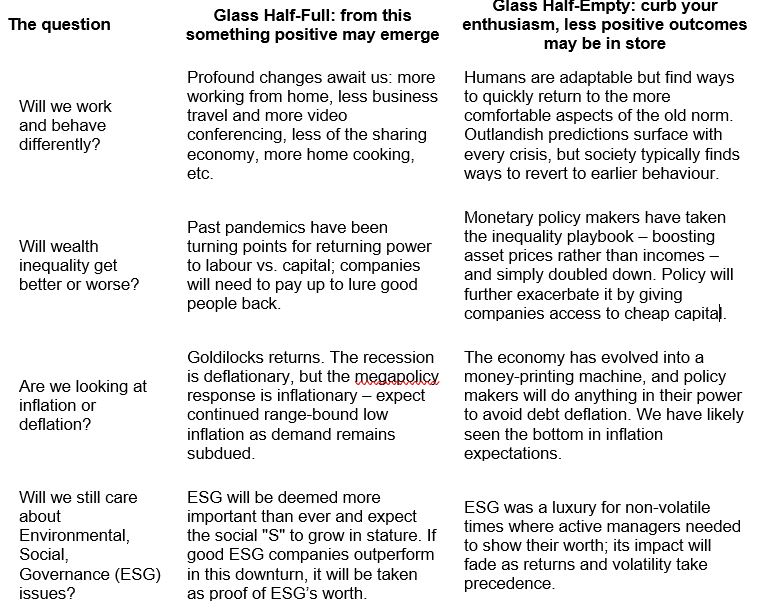

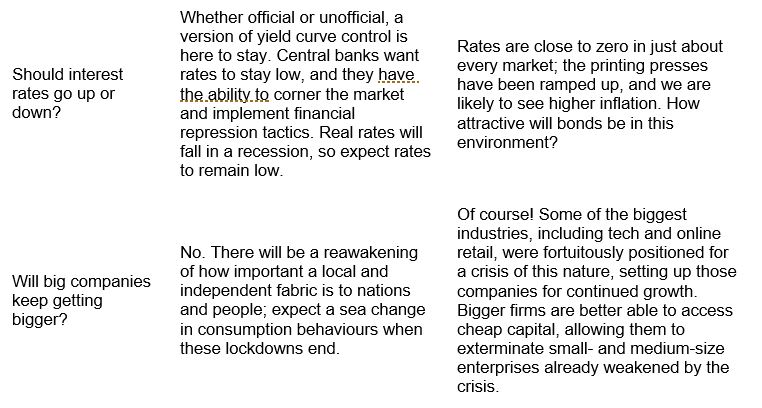

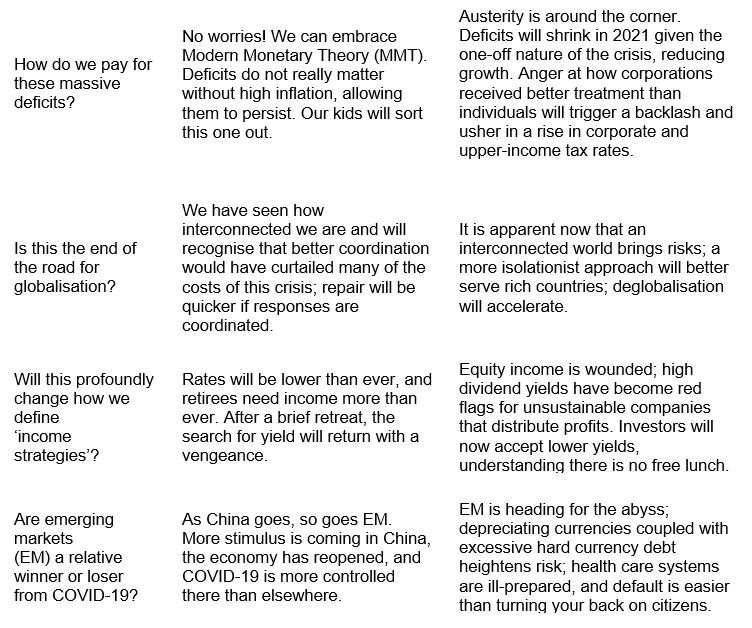

The below list of questions is by no means exhaustive, but an investor who can answer them will have the keys to unlock the market puzzle spread out before us. Each of these issues is generating a plethora of opinions. Perfectly valid arguments have sprung up on both sides of each. Here we summarise some of the questions we believe to be key and provide a snapshot of the dichotomy that exists among prognosticators.